Hike Flathead Lake on Phillips Trail #373. Phillips Trail #373 is 3.8 miles long and climbs about 600 feet; it intersects with Crane Mtn Road #498 and the Beardance Trail #76. This is one of three trails that climb up Crane Mountain. Access by car from Crane Mountain is available 4/1-11/30, otherwise hikers must access from the Flathead Lake side at the Beardance trailhead (4.4 miles up). The trail is open for the following uses: hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking.

Hike Flathead Lake on Phillips Trail #373. Phillips Trail #373 is 3.8 miles long and climbs about 600 feet; it intersects with Crane Mtn Road #498 and the Beardance Trail #76. This is one of three trails that climb up Crane Mountain. Access by car from Crane Mountain is available 4/1-11/30, otherwise hikers must access from the Flathead Lake side at the Beardance trailhead (4.4 miles up). The trail is open for the following uses: hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking.

Hike Flathead Lake

Usage: Light

Closest Towns: Bigfork

Directions:

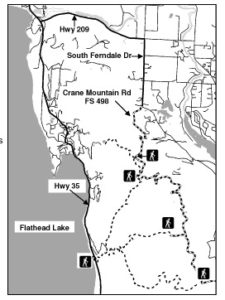

Crane Mtn Access: From Bigfork go south on Highway 35 for 0.7 miles, turning left onto Hwy 209. Stay on 209 for 3 miles, then turn right at the light onto South Ferndale Rd. After 2 miles merge right onto Crane Mountain Rd also called Forest Service Road #498. The trail is 3 miles up on the west side of the road.

Flathead Lake Access: From Bigfork follow Highway 35 south, past Woods Bay, to the Beardance Picnic Area south of mile marker 23. The trailhead is on the east side of the highway, across from the parking lot. If you are planning on vacationing around Flathead Lake, consider Mike’s Flathead Lake Vacation Guide.

Length : 3.8 miles

Elevation : 3,440 feet – 4,039 feet

This short, family friendly 0.4 mile loop interpretive Flathead Lake trail. The short but steep distance down to excellent view of Flathead Lake and the western skyline. This trail was developed in partnership with the Bigfork High School.

This short, family friendly 0.4 mile loop interpretive Flathead Lake trail. The short but steep distance down to excellent view of Flathead Lake and the western skyline. This trail was developed in partnership with the Bigfork High School. The Flathead Lake Bear Dance Trail is 6.7 miles long and climbs about 2,200 feet. It begins off of Highway # 35 from the Beardance Trailhead and follows Forest Road #10222 and terminates at Crane Mountain Road #498. The trail is open to: hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking.

The Flathead Lake Bear Dance Trail is 6.7 miles long and climbs about 2,200 feet. It begins off of Highway # 35 from the Beardance Trailhead and follows Forest Road #10222 and terminates at Crane Mountain Road #498. The trail is open to: hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking. Directions: From Bigfork go south on Highway 35 past Woods Bay and turn right after mile marker 23, entering the Beardance trailhead parking. The trailhead is on the east side of the highway.

Directions: From Bigfork go south on Highway 35 past Woods Bay and turn right after mile marker 23, entering the Beardance trailhead parking. The trailhead is on the east side of the highway.

Fees are charged during the summer (mid-May to late October). The Range is part of the U.S. Fee System and accepts Golden Passes and Federal Waterfowl Stamps. Pay fees at the Visitor Center. Camping is not allowed and the Range is closed at night.

Fees are charged during the summer (mid-May to late October). The Range is part of the U.S. Fee System and accepts Golden Passes and Federal Waterfowl Stamps. Pay fees at the Visitor Center. Camping is not allowed and the Range is closed at night. Glacier National Park is named for the glaciers that produced its landscape. A glacier is a moving mass of snow and ice. It forms when more snow falls each winter than melts in the summer. The snow accumulates and presses the layers below it into ice. The bottom layer of ice becomes flexible and therefore allows the glacier to move. As it moves, a glacier picks up rock and gravel. With this mixture of debris, it scours and sculptures the land it moves across. This is how, over thousands of years, Glacier National Park got all its valleys, sharp mountain peaks, and lakes. There are more than 50 glaciers in the park today, though they are smaller than the huge ones that existed 20,000 years ago.

Glacier National Park is named for the glaciers that produced its landscape. A glacier is a moving mass of snow and ice. It forms when more snow falls each winter than melts in the summer. The snow accumulates and presses the layers below it into ice. The bottom layer of ice becomes flexible and therefore allows the glacier to move. As it moves, a glacier picks up rock and gravel. With this mixture of debris, it scours and sculptures the land it moves across. This is how, over thousands of years, Glacier National Park got all its valleys, sharp mountain peaks, and lakes. There are more than 50 glaciers in the park today, though they are smaller than the huge ones that existed 20,000 years ago. The park is unique among US parks in its relationship with the Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada. The two parks meet at the border shared by the two countries. Though administered by separate countries, the parks are cooperatively managed in recognition that wild plants and animals ignore political boundaries and claim the natural and cultural resources on both sides of the border. In 1932, the parks were designated the first International Peace Park in recognition of the bonds of peace and friendship between the two nations. The two parks jointly share the name The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. Then, in 1995, The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park was designated for inclusion as a World Heritage Site.

The park is unique among US parks in its relationship with the Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada. The two parks meet at the border shared by the two countries. Though administered by separate countries, the parks are cooperatively managed in recognition that wild plants and animals ignore political boundaries and claim the natural and cultural resources on both sides of the border. In 1932, the parks were designated the first International Peace Park in recognition of the bonds of peace and friendship between the two nations. The two parks jointly share the name The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. Then, in 1995, The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park was designated for inclusion as a World Heritage Site. Recent archaeological surveys have found evidence of human use dating back over 10,000 years. These people may have been the ancestors of tribes that live in the area today. By the time the first European explorers came to this region, several different tribes inhabited the area. The Blackfeet Indians controlled the vast prairies east of the mountains. The Salish and Kootenai Indians lived and hunted in the western valleys. They also traveled east of the mountains to hunt buffalo.

Recent archaeological surveys have found evidence of human use dating back over 10,000 years. These people may have been the ancestors of tribes that live in the area today. By the time the first European explorers came to this region, several different tribes inhabited the area. The Blackfeet Indians controlled the vast prairies east of the mountains. The Salish and Kootenai Indians lived and hunted in the western valleys. They also traveled east of the mountains to hunt buffalo. The construction of the Going-to-the-Sun Road was a huge undertaking. Even today, visitors to the park marvel at how such a road could have been built. The final section of the Going-to-the-Sun Road, over Logan Pass, was completed in 1932 after 11 years of work. The road is considered an engineering feat and is a National Historic Landmark. It is one of the most scenic roads in North America. The construction of the road forever changed the way visitors would experience Glacier National Park. Future visitors would drive over sections of the park that previously had taken days of horseback riding to see.

The construction of the Going-to-the-Sun Road was a huge undertaking. Even today, visitors to the park marvel at how such a road could have been built. The final section of the Going-to-the-Sun Road, over Logan Pass, was completed in 1932 after 11 years of work. The road is considered an engineering feat and is a National Historic Landmark. It is one of the most scenic roads in North America. The construction of the road forever changed the way visitors would experience Glacier National Park. Future visitors would drive over sections of the park that previously had taken days of horseback riding to see.